“Steamboat whistles made a beautiful noise. Each vessel had her own more or less distinctive notes, and each hand upon the rope could pull forth a different voice: now a friendly nod of the head; a full tip of the hat; a screaming blast of annoyance punctuated with short silences; or a long, stentorian call that ranged and echoed o’er the valley. To the uninitiated, such as a visiting backwoods cousin, the sounds of river commerce were startling: sudden, shrill, felt as well as heard. Even a blasé pilot could start with surprise at a quick, powerful blast… Up and down the meandering Western Rivers, whistles were the sound of civilization,” – Charles Preston Fishbaugh, in From Paddlewheels to Propellors, pg. 59.

In this poetically written passage, historian Charles Fishbaugh captures the unique character, beauty, and grandeur of the steamboat whistle. Unless someone is lucky enough to live near a river town that has an authentic steamboat like the NATCHEZ in New Orleans or the BELLE OF LOUISVILLE in our own local area, there is a good chance that most people alive today have never heard this unique sound. This is a shame, because for more than a century steamboat whistles were one of the defining sounds of the river. In this article, we will examine the history and development of the steamboat whistle and tell a few interesting stories about this important piece of technology.

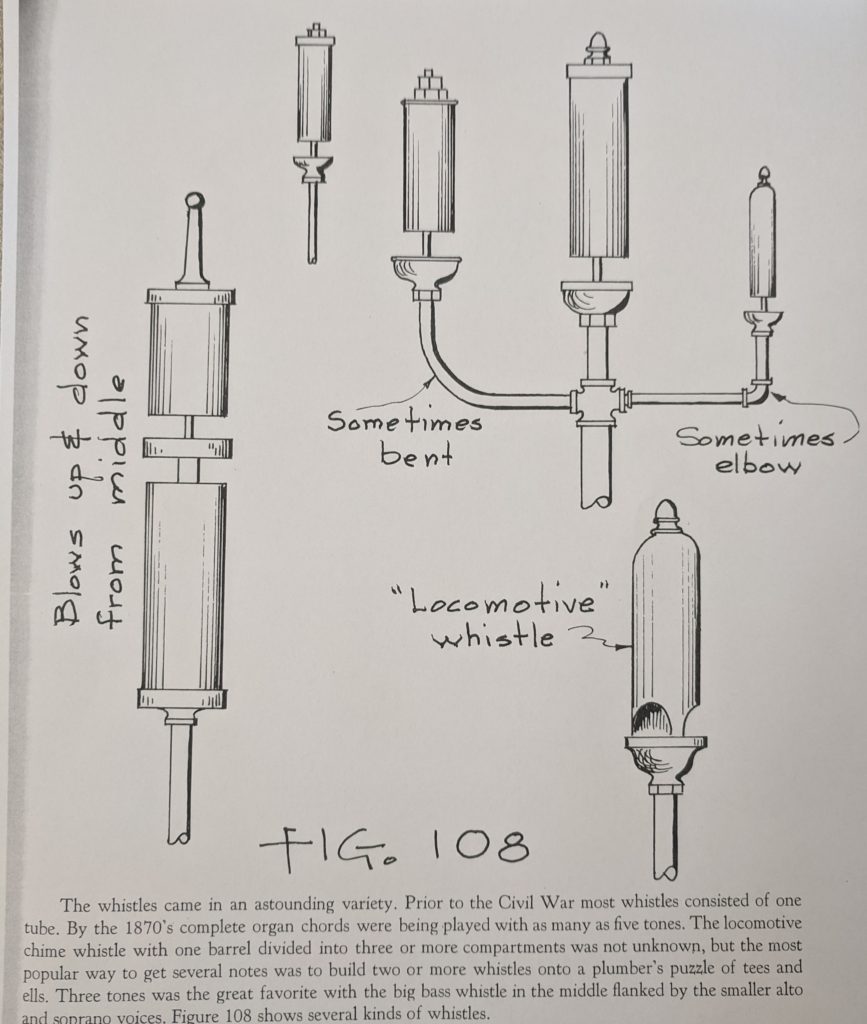

The steam whistle was first patented in England in 1838, though it had likely been in use from an earlier date. They originally saw use as low-pressure alarms on factory boilers in England and the United States. The use of pressurized steam to power them made these whistles significantly louder than most other forms of signaling available at the time; it also contributed to the steam whistle’s distinctive sound. As hot steam from the boilers blew through the whistle, the metal, usually brass, copper, iron, or another common metal of the day, expanded and contracted. This caused many semitones, overtones, and inversions of the pitch produced by the rushing steam. Differences in the size and construction of individual whistles’ bell lengths gave each of them a distinct musical quality, and astute listeners could tell boats apart from the sounds of their whistles alone.

According to steamboat historian Frederick Way Jr., the first documented use of a steam whistle on the Western Rivers was in 1844, when Chief Engineer John Stut Neal installed a whistle on the steamer REVENUE, built at Pittsburgh that same year. While it is possible that steam whistles were used on the river from an earlier date, Chief Neal deserves the official credit for beginning a new era of river communication. Throughout the rest of the 1840’s, whistles became a common feature on steamboats, and before long they could be heard up and down the inland rivers.

The steam whistle became the universal form of river communication in 1852, when Congress passed an act on river navigation and safety mandating its use. Before this, steamboat pilots communicated with each other primarily through a combination of shouts and bells. However, the human voice was simply not loud enough to be effective at signaling, and bells could easily be misunderstood or even not heard at all due to the impact of atmospheric conditions on their sound. This lack of effective signaling contributed to many collisions and accidents in the first several decades of the Steamboat Era. The steam whistle, with its greater volume and hard-to-miss sound, helped make the inland rivers a safer place, and its adoption was credited with a significant reduction in collision-related accidents.

Steamboat pilots used many different whistle signals while on the river, in effect creating a sort of second language between themselves. For example, one blast of the whistle from the pilot of a downbound boat (a boat steaming with the current and therefore having right-of-way) to the pilot of an upbound boat (a boat steaming against the current and having to yield to the downbound boat) indicated that the boats would pass on their port (left) sides, while two blasts from the downbound pilot signaled that the boats would pass on their starboard (right) sides. Another common signal was one long blast (the signal of a moored vessel preparing for departure) followed by three short blasts (the signal for a vessel operating under stern propulsion), indicating that a steamboat was about to leave the landing and back into the river.

In addition to these universal signals, pilots also used signals that were unique to each boat. This was so that people on the wharf could identify which boats were landing, often before they even came into view. The BELLE OF LOUISVILLE, which, launched in 1914, is the oldest inland river steamboat still in operation today, uses a pattern of one long blast, two short blasts, one long blast, and two short blasts for this very purpose.

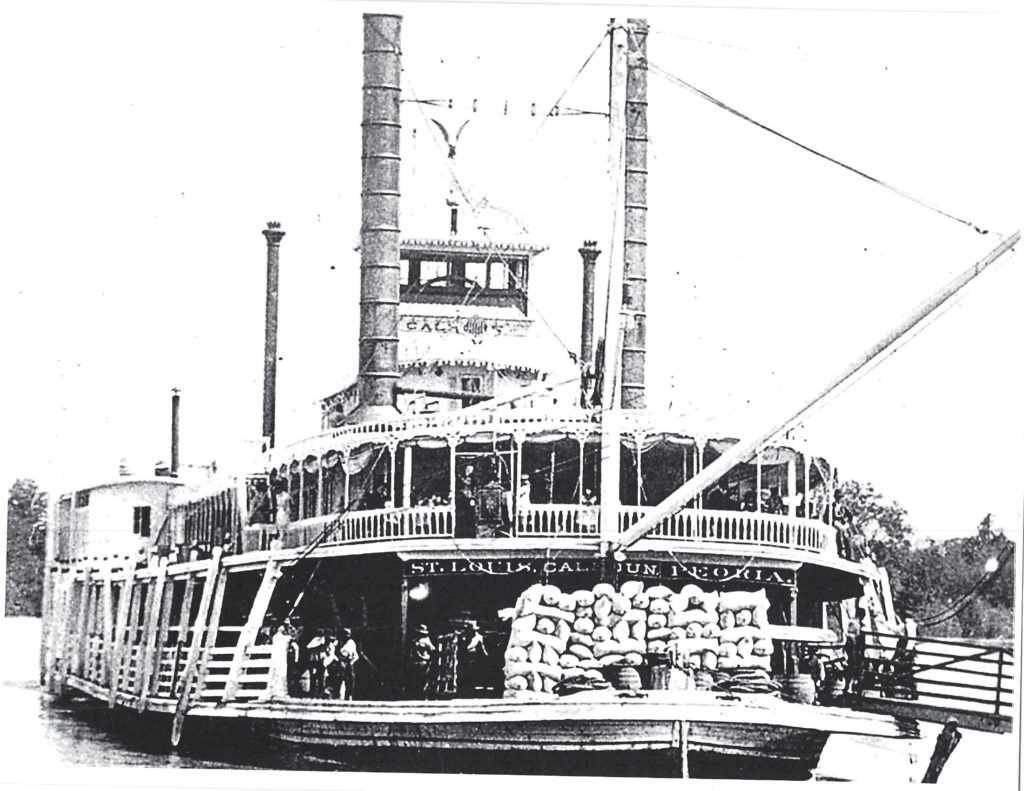

It was common for a steamboats’ whistle to outlive the boat itself, with many whistles being used on several different boats over a span of decades. An interesting example of this is the whistle from the steamer CALHOUN. Launched in 1876 at Jeffersonville, Indiana, CALHOUN spent most of her career working the St. Louis-Peoria packet trade on the Illinois River before being dismantled in 1892 at the Howard Shipyard in Madison, Indiana. (The Howard family of shipbuilders had multiple yards along the Ohio River during this time).

Later that same year, the Howards recycled CALHOUN’s whistle, in addition to much of her superstructure and machinery, when they built the steamer GREY EAGLE for the Eagle Packet Company. This company used CALHOUN’s whistle on several of their packet boats over the following decades. In 1923, they installed the whistle on the new steamer CAPE GIRARDEAU, the last steam packet boat built by the Howard family. CAPE GIRARDEAU later became the famous overnight boat GORDON C. GREENE, using the same whistle throughout her whole career until she herself sank in 1967.

The venerable old whistle then moved to the Ohio River Museum in Marietta, Ohio, where it remains to this day. For a brief, interesting period in 1980, however, it came out of retirement one final time to be used on the overnight boat MISSISSIPPI QUEEN for part of her cruising season. Although CALHOUN herself only existed for a couple of decades, for more than a hundred years her whistle was heard all along the inland rivers.

(Fun fact: The Howards themselves kept another memento of the CALHOUN after they dismantled her. To this day, visitors at the Howard Steamboat Museum can see the steamer’s decorative gold-gilt eagle from atop her pilothouse displayed in Edmonds Howards’ den).

Steam whistles were a ubiquitous sound on the inland rivers throughout the Steamboat Era. They were still a common sound even into the mid-20th Century, after the glory days of the era had passed. In our museum’s local area (the stretch of the Ohio River above and below Louisville, Kentucky), two familiar whistles during this time would have been found on the towboats J.R. NUGENT and EDITH NUGENT.

Both boats were owned by Nugent Sand & Gravel Company, and they show the variance in sound had between different types of whistles. J.R. NUGENT’s whistle, mounted on the port side of her pilothouse, was a unique Lonergan-pattern steam whistle that emitted a distinctive multi-note signal. EDITH NUGENT, on the other hand, had a large single-note whistle on the starboard side of her pilothouse that emitted one deep, powerful tone. Both boats operated out of Louisville throughout the 1940’s, and people all along this stretch of the Ohio River would have been familiar with the sound of their whistles.

As can be seen from even this handful of stories, the steam whistle was one of the defining sounds of the Steamboat Era. From its initial adoption as a signaling device in the 1840s through to the middle of the 20th Century, steam whistles were heard wherever a river was navigable. Although steamboats and the beautiful whistles they carried were eventually replaced with newer technology, there is still nothing quite like the sound of a steamboat giving a long, powerful blast of her whistle as she steams down the river.

If you would like to spend some time listening to iconic steamboat whistles like those on the BELLE OF LOUISVILLE, DELTA QUEEN, GORDON C. GREENE, and others, steamboats.org has a remarkable collection of whistle recordings at the following link below:

Sources:

Bates, Alan L. The Western Rivers Steamboat Cyclopedium. Hustle Press: Leonia. 1968.

Engstrom, Kadie. “Language of the River – Whistles”. (Educational Pamphlet). Howard Steamboat Museum.

Fishbaugh, Charles Preston. From Paddlewheels to Propellers. Indiana Historical Society: Indianapolis. 1970.

Hunter, Louis C. Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History. Harvard University Press: Cambridge. 1949.

Morrison, John H. History of American Steam Navigation. Stephen Daye Press: New York. 1958.

Vasconcelos, Travis. “Curator’s Corner: Steam Whistles”. (Educational video). Howard Seamboat Museum. (Posted to Facebook September 4th, 2020).

Way Jr., Frederick. Way’s Packet Directory, 1848-1983. Ohio University Press: Athens. 1983.

” — ” Way’s Steam Towboat Directory. Ohio University Press: Athens. 1990.